Go full throttle: The essentials of throttling in your application architecture

Five scenarios for planning a service-oriented architecture or microservices architecture

First published Published May 31, 2017 and Updated June 1, 2017

Throttling is the threshold for limiting the number of requests to a component. This threshold is important wherever an invocation chain passes through several distributed components. For example, a call passes from an API consumer through various layers of the architecture before it reaches the system of record where the server responds to the request. If throttling is not configured correctly, the infrastructure is at risk of accidental or malicious overload. By taking time to correctly design the throttling implementation, you can dramatically reduce this risk.

Five scenarios for planning a service-oriented architecture or microservices architecture

First published Published May 31, 2017 and Updated June 1, 2017

Throttling is the threshold for limiting the number of requests to a component. This threshold is important wherever an invocation chain passes through several distributed components. For example, a call passes from an API consumer through various layers of the architecture before it reaches the system of record where the server responds to the request. If throttling is not configured correctly, the infrastructure is at risk of accidental or malicious overload. By taking time to correctly design the throttling implementation, you can dramatically reduce this risk. This article covers throttling concepts and key considerations for five throttling scenarios. It describes throttling in the context of a service-oriented architecture (SOA) or microservices architecture. For example, you can use throttling to protect a service host or to limit a user to the agreed service-level agreement (SLA).

Terminology

To help you understand throttling and the scenarios that are presented in this article, you must understand the following terms:

- Service/API: A provider that can also be a consumer, such as a composite service.

- Consumer Application: An application that invokes a service but does not provide a service.

- Consumer: An instance of a service, API, or application that calls an endpoint of a service or API.

- Provider: An instance of service or API that exposes an endpoint to be consumed.

- Composite service: A single request by a consumer that is fulfilled by the enterprise service bus (ESB) by invoking several provider services.

- Maximum capacity (not enforced): If the rate of messages is equal to or greater than this number, the infrastructure goes down or messages become lost.

An overview of throttling

Throttling is configured as a threshold on the maximum number of requests that can be made during a specific time period. For example, a throttle can be defined as a maximum number of requests per second, a maximum number of requests per day, or both.

When a threshold is reached, more requests arrive than can be processed. The throttled messages must be queued or rejected. If a queuing solution is implemented, all messages are put into a first-in first-out (FIFO) queue. When the service has capacity, it retrieves messages from this queue and processes them. When the request rate is greater, the available capacity messages are processed in order and are not lost. If a rejection solution is implemented and no spare capacity is available, messages are discarded.

Types of throttling

Throttling comes in two forms:

- Provider throttling: Is used to protect the provider infrastructure. The maximum rate of messages for a provider must be less than the infrastructure can support.

- Consumer throttling: Is based on the SLA contract between the consuming application, API, or service and the providing service or API. The SLA also dictates the maximum rate of consumption between the consumer and provider. Consumer throttling is also used to ensure that the consumer accesses the service only as agreed.

A service or API can be both a consumer and a provider. However, an application can only be a consumer. The following sections highlight the complexities of five scenarios to provide a basic understanding of the risks when you use throttling.

Scenario 1: Provider-only throttling (simple scenario)

Provider-only throttling is commonly used throughout the industry. Infrastructure designers tend to believe that they can protect their business if they manage the incoming traffic to each service.

If you use provider-only throttling, the SLA is not enforced. In this case, a single consumer can use 100% of the infrastructure to the detriment of the other consumers. In addition, no tracking is available to help size future capacity requirements for the provider service or API.

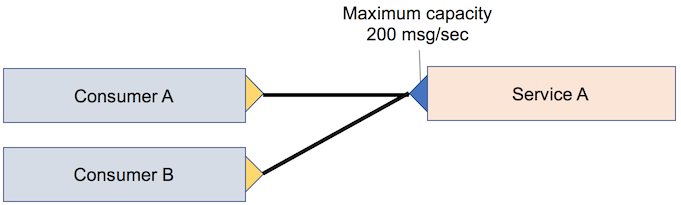

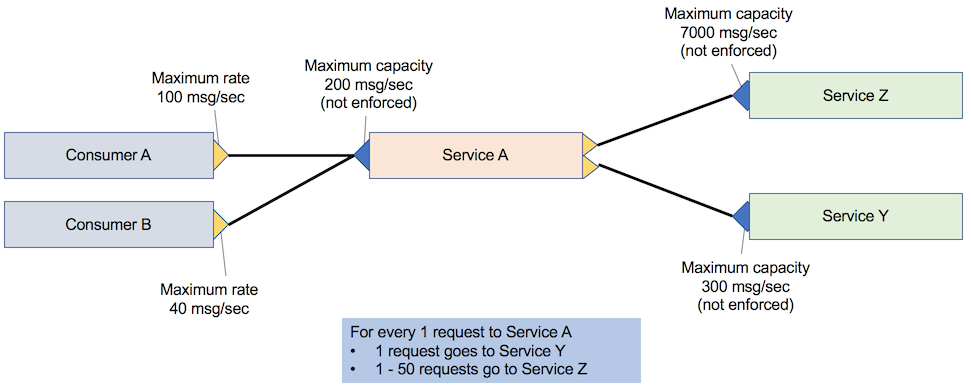

The difficulty here is that the consumer has no limits and the provider does. Therefore, if consumer requests exceed the provider throttle threshold, messages are discarded or queued, which can cause failures or worsen performance for the consumer. However, you can track (or log) the number of consumer and provider requests. The following figure shows an example of provider-only throttling. It illustrates a single provider service that is throttled and two consumers.

Scenario 2: Consumer-only throttling (simple scenario)

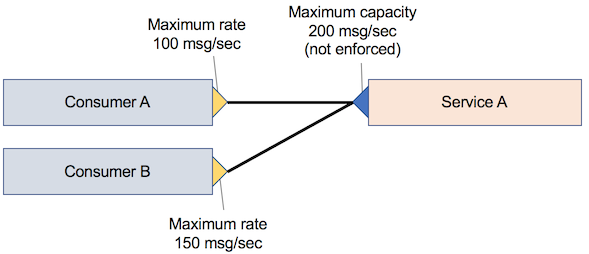

If you use consumer-only throttling, the throughput that reaches the service provider is not clearly enforced. For example, consumer A requests an SLA that details a peak of 100 messages per second to provider A, and consumer B requests an SLA that details a peak of 150 messages per second. In this case, the provider must be able to send 250 messages per second. However, because these values are both peaks, they might not be required at the same time. Therefore, a lower provider capacity might be sufficient. The following figure shows a simple scenario of consumer-only throttling.

The difficulty in this scenario is that the consumer is limited, but the provider is not. If the consumer SLAs are well set, the providers will never be overloaded. This situation is not simple to arrange, and some provider services can become overloaded. However, you can track (or log) the number of consumer and provider requests.

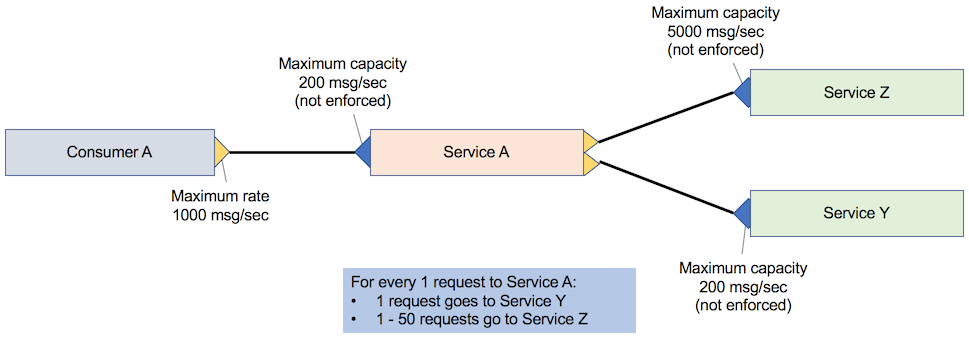

Scenario 3: Application consumer-only throttling (composite scenario)

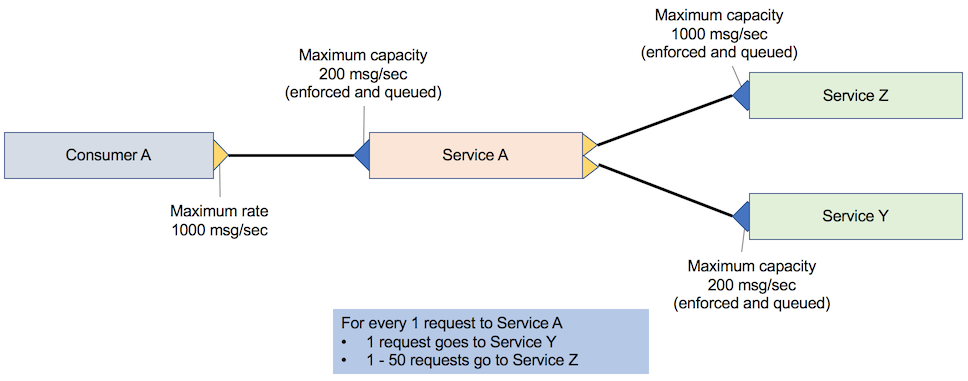

In application consumer-only throttling, service A calls both service Z and service Y before it responds to consumer A. For each request to service A, service A makes a request to service Y and 1 – 50 requests to service Z, depending on the attributes that are passed to service A. The following figure shows a single service that is called by a single consumer and depends on two back-end services. The consumer is limited to 1,000 messages per second, but the downstream services cannot handle that quantity of load.

When you negotiate this SLA, the capacity of service A is validated. However, it is often impractical to validate all dependencies of service A. As shown in the following diagram, when a new application (consumer B) is registered, it has a new SLA with service A.

Consider an example where you add consumer B with its requirements of 40 messages per second alongside consumer A with the requirement of 100 messages per second. In this case, service Y must be able to handle 140 messages per second, and service Z must be able to handle 7000 messages per second. Although service Z will get called 1 – 50 times per request from service A, you must ensure that the infrastructure can handle the full load because you do not have any protection. You must scale out service Z significantly, even though it might never be fully used.

By adding throttling between service A and service Z, the platform can be released without initially scaling out service Z. Service Z can then be scaled out in the future if required.

Scenario 4. Application consumer and service API provider-only throttling (composite scenario)

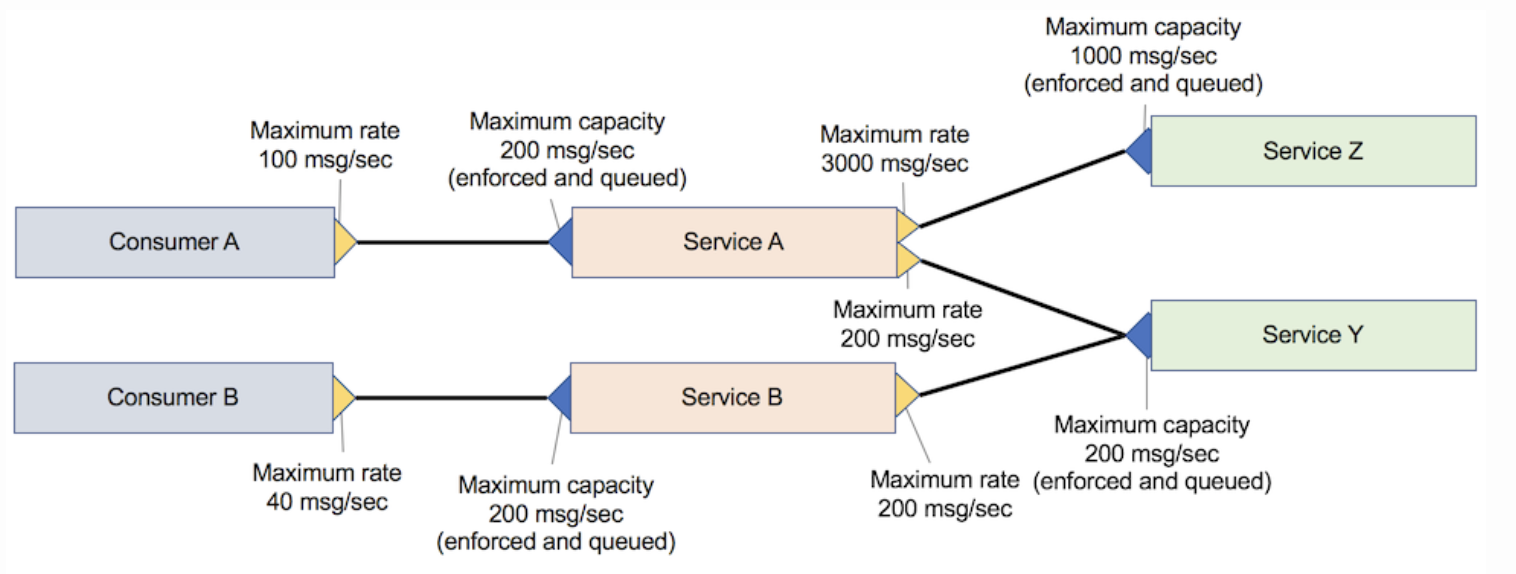

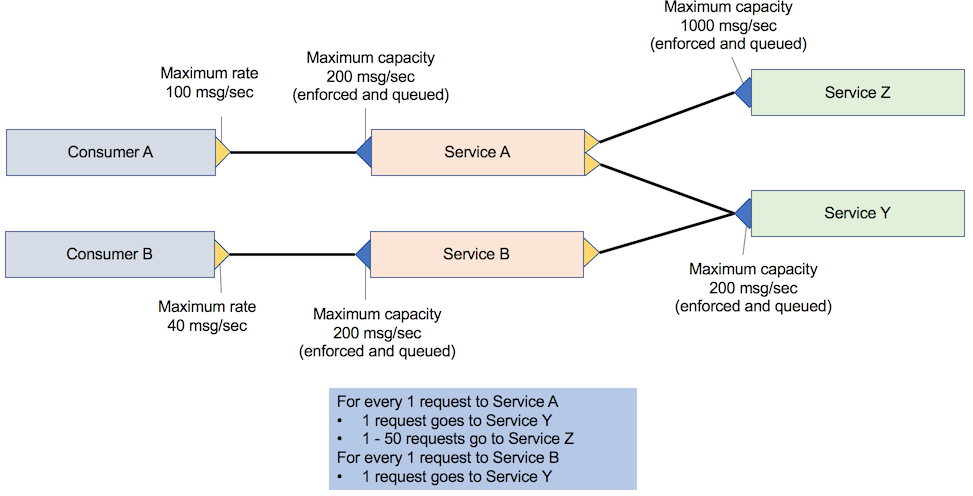

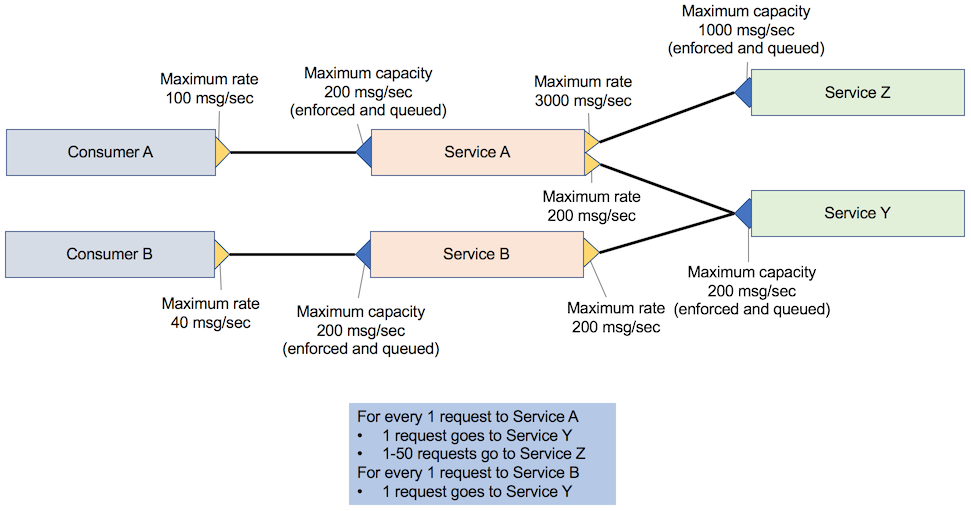

For each request to service A, service A makes one request to service Y and 1 – 50 requests to service Z, depending on the attributes that are passed to service A. This scenario is referred to as application consumer and service API provider-only throttling. Services A, Y, and Z have a rate that limits the implementation that queues the request if the rate limit goes above the desired threshold.

Consumer A calls service A, which in turn calls service Z and service Y. Consumer B calls service B, which invokes service Y. The following figure illustrates this scenario.

However, when service A reaches its peak throughput, the quality of service B calling service Y might drop significantly because its requests are queued. To avoid this drop in quality, the maximum capacity of service Y must be higher than service A or service B, depending on which service has the higher capacity.

If a new consumer (consumer C) is added that calls service B, and service B is scaled to see this requirement, service Y cannot guarantee that it can handle the increased number of requests at peak. Because no formal SLA exists between service B and service Y, service B can increase the number of requests to service Y at any time.

Scenario 5. Full throttling support (composite scenario)

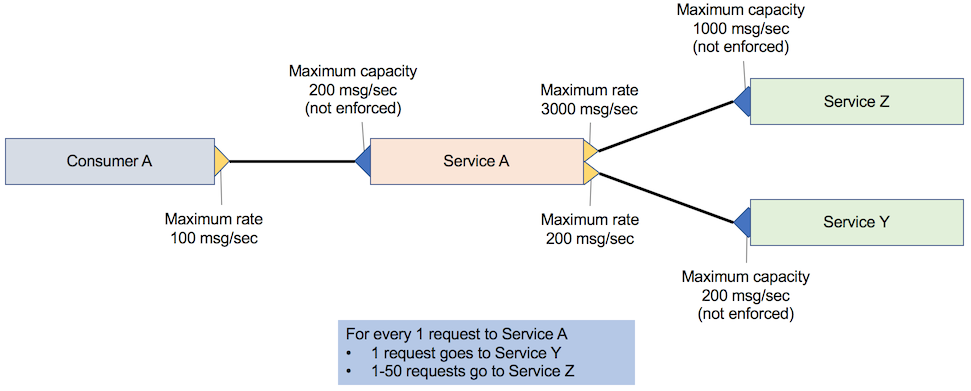

For each request to service A, service A makes a request to service Y and 1 – 50 requests to service Z, depending on the attributes that are passed to service A as shown in the following figure. This scenario provides full throttling support.

Consumer-level throttling is applied between services A and B and services Z and Y. That is, if you increase the throughput of service B, it does not automatically increase the load of service Y. Therefore, you must renegotiate the SLA between service B and service Y before service B can run at maximum capacity. The following figure shows a scenario where all providers and all consumers are throttled.

Conclusion

This article highlighted the key concepts of throttling and provided guidance for five throttling scenarios. It showed examples of the importance of both consumer and provider throttling. By configuring throttling correctly, you can greatly reduce the risk of accidental or malicious overload in your infrastructure.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Kim Clark, Integration Portfolio Architect for IBM UK, for his assistance in reviewing this article.